string OperationsThe string type provides a number of additional operations beyond those common to the sequential containers. For the most part, these additional operations either support the close interaction between the string class and C-style character arrays, or they add versions that let us use indices in place of iterators.

The string library defines a great number of functions. Fortunately, these functions use repeated patterns. Given the number of functions supported, this section can be mind-numbing on first reading; so readers might want to skim it. Once you know what kinds of operations are available, you can return for the details when you need to use a particular operation.

strings

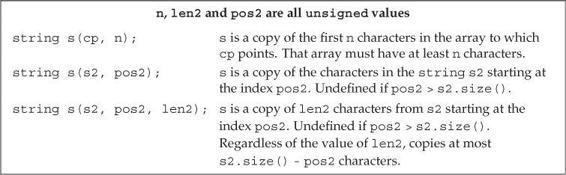

In addition to the constructors we covered in § 3.2.1 (p. 84) and to the constructors that string shares with the other sequential containers (Tables 9.3 (p. 335)) the string type supports three more constructors that are described in Table 9.11.

Table 9.11. Additional Ways to Construct strings

The constructors that take a string or a const char* take additional (optional) arguments that let us specify how many characters to copy. When we pass a string, we can also specify the index of where to start the copy:

const char *cp = "Hello World!!!"; // null-terminated array

char noNull[] = {'H', 'i'}; // not null terminated

string s1(cp); // copy up to the null in cp; s1 == "Hello World!!!"

string s2(noNull,2); // copy two characters from no_null; s2 == "Hi"

string s3(noNull); // undefined: noNull not null terminated

string s4(cp + 6, 5);// copy 5 characters starting at cp[6]; s4 == "World"

string s5(s1, 6, 5); // copy 5 characters starting at s1[6]; s5 == "World"

string s6(s1, 6); // copy from s1 [6] to end of s1; s6 == "World!!!"

string s7(s1,6,20); // ok, copies only to end of s1; s7 == "World!!!"

string s8(s1, 16); // throws an out_of_range exception

Ordinarily when we create a string from a const char*, the array to which the pointer points must be null terminated; characters are copied up to the null. If we also pass a count, the array does not have to be null terminated. If we do not pass a count and there is no null, or if the given count is greater than the size of the array, the operation is undefined.

When we copy from a string, we can supply an optional starting position and a count. The starting position must be less than or equal to the size of the given string. If the position is greater than the size, then the constructor throws an out_of_range exception (§ 5.6, p. 193). When we pass a count, that many characters are copied, starting from the given position. Regardless of how many characters we ask for, the library copies up to the size of the string, but not more.

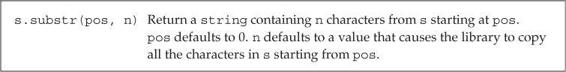

substr OperationThe substr operation (described in Table 9.12) returns a string that is a copy of part or all of the original string. We can pass substr an optional starting position and count:

string s("hello world");

string s2 = s.substr(0, 5); // s2 = hello

string s3 = s.substr(6); // s3 = world

string s4 = s.substr(6, 11); // s3 = world

string s5 = s.substr(12); // throws an out_of_range exception

Table 9.12. Substring Operation

The substr function throws an out_of_range exception (§ 5.6, p. 193) if the position exceeds the size of the string. If the position plus the count is greater than the size, the count is adjusted to copy only up to the end of the string.

Exercises Section 9.5.1

Exercise 9.41: Write a program that initializes a

stringfrom avector<char>.Exercise 9.42: Given that you want to read a character at a time into a

string, and you know that you need to read at least 100 characters, how might you improve the performance of your program?

string

The string type supports the sequential container assignment operators and the assign, insert, and erase operations (§ 9.2.5, p. 337, § 9.3.1, p. 342, and § 9.3.3, p. 348). It also defines additional versions of insert and erase.

In addition to the versions of insert and erase that take iterators, string provides versions that take an index. The index indicates the starting element to erase or the position before which to insert the given values:

s.insert(s.size(), 5, '!'); // insert five exclamation points at the end of s

s.erase(s.size() - 5, 5); // erase the last five characters from s

The string library also provides versions of insert and assign that take C-style character arrays. For example, we can use a null-terminated character array as the value to insert or assign into a string:

const char *cp = "Stately, plump Buck";

s.assign(cp, 7); // s == "Stately"

s.insert(s.size(), cp + 7); // s == "Stately, plump Buck"

Here we first replace the contents of s by calling assign. The characters we assign into s are the seven characters starting with the one pointed to by cp. The number of characters we request must be less than or equal to the number of characters (excluding the null terminator) in the array to which cp points.

When we call insert on s, we say that we want to insert the characters before the (nonexistent) element at s[size()]. In this case, we copy characters starting seven characters past cp up to the terminating null.

We can also specify the characters to insert or assign as coming from another string or substring thereof:

string s = "some string", s2 = "some other string";

s.insert(0, s2); // insert a copy of s2 before position 0 in s

// insert s2.size() characters from s2 starting at s2[0] before s[0]

s.insert(0, s2, 0, s2.size());

append and replace FunctionsThe string class defines two additional members, append and replace, that can change the contents of a string. Table 9.13 summarizes these functions. The append operation is a shorthand way of inserting at the end:

string s("C++ Primer"), s2 = s; // initialize s and s2 to "C++ Primer"

s.insert(s.size(), " 4th Ed."); // s == "C++ Primer 4th Ed."

s2.append(" 4th Ed."); // equivalent: appends " 4th Ed." to s2; s == s2

Table 9.13. Operations to Modify strings

The replace operations are a shorthand way of calling erase and insert:

// equivalent way to replace "4th" by "5th"

s.erase(11, 3); // s == "C++ Primer Ed."

s.insert(11, "5th"); // s == "C++ Primer 5th Ed."

// starting at position 11, erase three characters and then insert "5th"

s2.replace(11, 3, "5th"); // equivalent: s == s2

In the call to replace, the text we inserted happens to be the same size as the text we removed. We can insert a larger or smaller string:

s.replace(11, 3, "Fifth"); // s == "C++ Primer Fifth Ed."

In this call we remove three characters but insert five in their place.

stringThe append, assign, insert, and replace functions listed Table 9.13 have several overloaded versions. The arguments to these functions vary as to how we specify what characters to add and what part of the string to change. Fortunately, these functions share a common interface.

The assign and append functions have no need to specify what part of the string is changed: assign always replaces the entire contents of the string and append always adds to the end of the string.

The replace functions provide two ways to specify the range of characters to remove. We can specify that range by a position and a length, or with an iterator range. The insert functions give us two ways to specify the insertion point: with either an index or an iterator. In each case, the new element(s) are inserted in front of the given index or iterator.

There are several ways to specify the characters to add to the string. The new characters can be taken from another string, from a character pointer, from a brace-enclosed list of characters, or as a character and a count. When the characters come from a string or a character pointer, we can pass additional arguments to control whether we copy some or all of the characters from the argument.

Not every function supports every version of these arguments. For example, there is no version of insert that takes an index and an initializer list. Similarly, if we want to specify the insertion point using an iterator, then we cannot pass a character pointer as the source for the new characters.

Exercises Section 9.5.2

Exercise 9.43: Write a function that takes three

strings,s,oldVal, andnewVal. Using iterators, and theinsertanderasefunctions replace all instances ofoldValthat appear insbynewVal. Test your function by using it to replace common abbreviations, such as “tho” by “though” and “thru” by “through”.Exercise 9.44: Rewrite the previous function using an index and

replace.Exercise 9.45: Write a funtion that takes a

stringrepresenting a name and two otherstrings representing a prefix, such as “Mr.” or “Ms.” and a suffix, such as “Jr.” or “III”. Using iterators and theinsertandappendfunctions, generate and return a newstringwith the suffix and prefix added to the given name.Exercise 9.46: Rewrite the previous exercise using a position and length to manage the

strings. This time use only theinsertfunction.

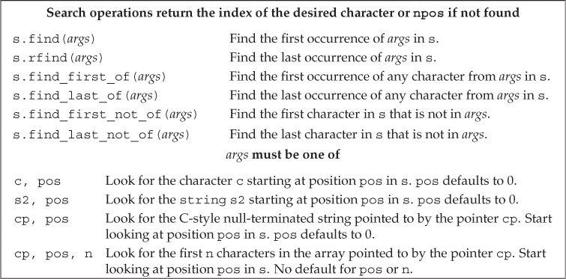

string Search Operations

The string class provides six different search functions, each of which has four overloaded versions. Table 9.14 describes the search members and their arguments. Each of these search operations returns a string::size_type value that is the index of where the match occurred. If there is no match, the function returns a static member (§ 7.6, p. 300) named string::npos. The library defines npos as a const string::size_type initialized with the value -1. Because npos is an unsigned type, this initializer means npos is equal to the largest possible size any string could have (§ 2.1.2, p. 35).

Table 9.14. string Search Operations

The

stringsearch functions returnstring::size_type, which is anunsignedtype. As a result, it is a bad idea to use anint, or other signed type, to hold the return from these functions (§ 2.1.2, p. 36).

The find function does the simplest search. It looks for its argument and returns the index of the first match that is found, or npos if there is no match:

string name("AnnaBelle");

auto pos1 = name.find("Anna"); // pos1 == 0

returns 0, the index at which the substring "Anna" is found in "AnnaBelle".

Searching (and other string operations) are case sensitive. When we look for a value in the string, case matters:

string lowercase("annabelle");

pos1 = lowercase.find("Anna"); // pos1 == npos

This code will set pos1 to npos because Anna does not match anna.

A slightly more complicated problem requires finding a match to any character in the search string. For example, the following locates the first digit within name:

string numbers("0123456789"), name("r2d2");

// returns 1, i.e., the index of the first digit in name

auto pos = name.find_first_of(numbers);

Instead of looking for a match, we might call find_first_not_of to find the first position that is not in the search argument. For example, to find the first nonnumeric character of a string, we can write

string dept("03714p3");

// returns 5, which is the index to the character 'p'

auto pos = dept.find_first_not_of(numbers);

We can pass an optional starting position to the find operations. This optional argument indicates the position from which to start the search. By default, that position is set to zero. One common programming pattern uses this optional argument to loop through a string finding all occurrences:

string::size_type pos = 0;

// each iteration finds the next number in name

while ((pos = name.find_first_of(numbers, pos))

!= string::npos) {

cout << "found number at index: " << pos

<< " element is " << name[pos] << endl;

++pos; // move to the next character

}

The condition in the while resets pos to the index of the first number encountered, starting from the current value of pos. So long as find_first_of returns a valid index, we print the current result and increment pos.

Had we neglected to increment pos, the loop would never terminate. To see why, consider what would happen if we didn’t do the increment. On the second trip through the loop we start looking at the character indexed by pos. That character would be a number, so find_first_of would (repeatedly) returns pos!

The find operations we’ve used so far execute left to right. The library provides analogous operations that search from right to left. The rfind member searches for the last—that is, right-most—occurrence of the indicated substring:

string river("Mississippi");

auto first_pos = river.find("is"); // returns 1

auto last_pos = river.rfind("is"); // returns 4

find returns an index of 1, indicating the start of the first "is", while rfind returns an index of 4, indicating the start of the last occurrence of "is".

Similarly, the find_last functions behave like the find_first functions, except that they return the last match rather than the first:

•

find_last_ofsearches for the last character that matches any element of the searchstring.

•

find_last_not_ofsearches for the last character that does not match any element of the searchstring.

Each of these operations takes an optional second argument indicating the position within the string to begin searching.

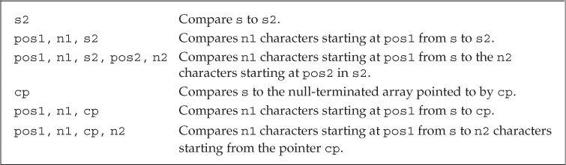

compare Functions

In addition to the relational operators (§ 3.2.2, p. 88), the string library provides a set of compare functions that are similar to the C library strcmp function (§ 3.5.4, p. 122). Like strcmp, s.compare returns zero or a positive or negative value depending on whether s is equal to, greater than, or less than the string formed from the given arguments.

Exercises Section 9.5.3

Exercise 9.47: Write a program that finds each numeric character and then each alphabetic character in the

string "ab2c3d7R4E6". Write two versions of the program. The first should usefind_first_of, and the secondfind_first_not_of.Exercise 9.48: Given the definitions of

nameandnumberson page 365, what doesnumbers.find(name)return?Exercise 9.49: A letter has an ascender if, as with

dorf, part of the letter extends above the middle of the line. A letter has a descender if, as withporg, part of the letter extends below the line. Write a program that reads a file containing words and reports the longest word that contains neither ascenders nor descenders.

As shown in Table 9.15, there are six versions of compare. The arguments vary based on whether we are comparing two strings or a string and a character array. In both cases, we might compare the entire string or a portion thereof.

Table 9.15. Possible Arguments to s.compare

Strings often contain characters that represent numbers. For example, we represent the numeric value 15 as a string with two characters, the character '1' followed by the character '5'. In general, the character representation of a number differs from its numeric value. The numeric value 15 stored in a 16-bit short has the bit pattern 0000000000001111, whereas the character string "15" represented as two Latin-1 chars has the bit pattern 0011000100110101. The first byte represents the character '1' which has the octal value 061, and the second byte represents '5', which in Latin-1 is octal 065.

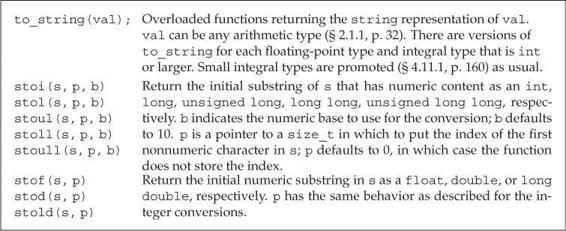

The new standard introduced several functions that convert between numeric data and library strings:

int i = 42;

string s = to_string(i); // converts the int i to its character representation

double d = stod(s); // converts the string s to floating-point

Table 9.16. Conversions between strings and Numbers

Here we call to_string to convert 42 to its corresponding string representation and then call stod to convert that string to floating-point.

The first non-whitespace character in the string we convert to numeric value must be a character that can appear in a number:

string s2 = "pi = 3.14";

// convert the first substring in s that starts with a digit, d = 3.14

d = stod(s2.substr(s2.find_first_of("+-.0123456789")));

In this call to stod, we call find_first_of (§ 9.5.3, p. 364) to get the position of the first character in s that could be part of a number. We pass the substring of s starting at that position to stod. The stod function reads the string it is given until it finds a character that cannot be part of a number. It then converts the character representation of the number it found into the corresponding double-precision floating-point value.

The first non-whitespace character in the string must be a sign (+ or -) or a digit. The string can begin with 0x or 0X to indicate hexadecimal. For the functions that convert to floating-point the string may also start with a decimal point (.) and may contain an e or E to designate the exponent. For the functions that convert to integral type, depending on the base, the string can contain alphabetic characters corresponding to numbers beyond the digit 9.

If the

stringcan’t be converted to a number, These functions throw aninvalid_argumentexception (§ 5.6, p. 193). If the conversion generates a value that can’t be represented, they throwout_of_range.